FROM THE GRAND HÔTEL CONTINENTAL

to the Collectivity of Corsica

First

Ajaccio, winter resort

According to the chroniclers, it was doctors who led to the advent of Ajaccio as a tourist resort.

As early as 1852, famous practitioners began to extol the city’s natural riches, but above all the quality and healing powers of its climate. Then came the “founders” of the resort. They took the lead by promoting the reception and accommodation of the first over-winterers, especially the English and the Germans. The construction of renowned hotels and the visits of prominent personalities from the European aristocracy established the reputation and prestige of the imperial city. The dream then became reality. Built as a leading winter resort, Ajaccio remained so until 1912 – two years before the First World War.

POSTER David Dellepiane (1866‐1932) Ajaccio – Corsica

© CdC, Musée de la Corse/Christian Andreani

By demonstrating the superiority of its climate, doctors were the origin of the project “Ajaccio, winter resort”. First among them was Dr Donné, Rector of the Montpellier Academy. Delighted with the beneficial influence of the Ajaccian climate on his wife’s illness, he wrote an article in the “Journal des Débats” of 15 February 1852. “I do not know”, he wrote, “of a city better located, prettier and more joyful than Ajaccio”. Ten years later, an English doctor, Dr Bennet, followed suit by saying that Ajaccio was “one of the most beautiful places in Europe, with a much better climate than the Riviera”; imitated successively, in 1864 and 1868, by two other colleagues, the English Ribton and the German Biermann.

Meanwhile, Dr de Pietra Santa, one of the Emperor’s doctors, was officially commissioned by Napoleon III to carry out a climatological study in Ajaccio. A four-month study which led, in 1868, to the publication under his name of a book entitled “La Corse et la station d’Aiacciu” (“Corsica and the Resort of Ajaccio”) in which he wrote that the city “also offers, through its mineral waters, very valuable resources for invalids, which are added to the climatological conditions and which mark out the most brilliant future for the new resort.” So, attracted by the many virtues of this land, the compatriots of these English and German doctors soon came to discover this much-vaunted Ajaccio climate.

1868: a decisive year for the promotion of Ajaccio as a winter resort. But with the arrival of the first over-winterers, the lack of accommodation facilities became evident. It was then that three personalities would “rise to the occasion” to try to remedy this situation and thus emerge as the real promoters of island climate tourism.

First, Count Bacciochi, Grand Chamberlain and Superintendent General of the Imperial Theatres. It was he who laid the foundations for the winter resort project by deciding in 1862 to build four cottages in his home town, and obtaining a maritime link between Nice and Ajaccio from the government.

The second personality was none other than Miss Thomasina Campbell, a famous British citizen and Scottish landowner, who was said to be so “eager to see Ajaccio turn into a winter resort” that she redoubled her projects and actions without ever giving in to the Administration’s inertia.

The proof was the construction of the Anglican Holy Trinity Church, carried out at her own expense and under her care in 1878, on the Cours Grandval.

Her “Notes on the Island of Corsica”, published in 1868, were like invitations to her readers. “Follow me!” she wrote. “(…) The scenery is far too beautiful and too grand for me to dream that I could do it justice. The best advice to be given is to say, ‘Come, and judge for yourself.'”

Finally, Count Multedo, to whom Ajaccio owes the opening and ownership of the current Boulevard Sylvestre Marcaggi, which still today is called the “Foreigners’ Quarter”.

It was not until 1877 that the Prefect Grandval approved the creation of the association “Ajaccio, winter resort” at the instigation of ten personalities including Dr Frasseto, the banker Lanzi, the architect Maglioli, the English major Murray and the bookseller Rocca Tartarini. Its goal was to facilitate the accommodation and stay of foreigners in the city. The association became a tourism promotion initiative in 1904.

Tea time

in Aiacciu

The first winter visitors would be mainly foreigners, in the wake of famous personalities such as Major Murray, Miss Thomasina Campbell and the painter Edward Lear who would give revealing testimony of their enthusiasm for Ajaccio after their stay on the island. They would be pensioners in search of exoticism and the picturesque, most often accompanied by their servants. Their travel stories are a wealth of information and observations on common themes. Surprised that Corsica did not enjoy greater renown, Miss Campbell proved to be the best propagandist for the island: “It seems incredible that the mountains, mines, marbles and mineral waters that abound should be so little known – that a climate so delightfully mild and yet invigorating, is so little sought.” She would not be satisfied with just being surprised. She went so far as to denounce the causes of this lack of awareness of Corsica. “It is the fashion on the Riviera,” she wrote, “to abuse Corsica, and to predict all kinds of fevers and misfortunes to those who visit it. I speak from experience; and I think all who may be induced to brave these old women’s tales, will thank me for setting the example. (…)” Installed in Ajaccio, Miss Campbell would come across the British painter Edward Lear, an experienced traveller whose publications on Italy and Albania had won such success that his audience awaited with impatience the account of his trip to Corsica. His first impressions would be those of an artist who would highlight the absence of architectural remains in a setting of natural magnificence.

But after having crisscrossed the island, his first impression would change significantly and he would confess that so many wonders seemed made for the painter: “The island offers the painter who lives there an infinite field of investigation.” If Miss Campbell was enthusiastic about a “charming” seashore made of “many shells, very fine sand and very beautiful rocks” unlike Nice, “where you have heavy shingle, and many washerwomen”, Edward Lear would enjoy the future Grandval course – which would later become the Foreigners’ Quarter – where, according to Miss Campbell, horse races were held on 12, 13 and 14 May, on the occasion of the fair of St. Pancras – and the Route des Sanguinaires, which completed the connection of Vignola with the Parata Tower.

Foreigners and continental visitors on holiday in Ajaccio would not fail to visit Napoleon’s birthplace with a sense of excitement. According to Miss Campbell, “Every person coming to Ajaccio will be desirious of seeing the house where Napoleon was born…

It is to be hoped that the city of Ajaccio will want to preserve the few relics that recall the childhood days of the Great Man, whose name alone honours Ajaccio and Corsica.”

A legitimate concern because, when Prince Roland Bonaparte made a trip to Corsica in 1887, the Emperor’s birthplace was rented to an English family!

Émile Bergerat, who accompanied him, was offended by such a lack of regard on the part of the Ajaccians: “Oh! This almost sacred residence exploited as a rental house! The feeling is still harsh (…)” In 1913, René Bazin, who consulted the visitors’ register, noted the passage of Edward VII, the Queen of England and Princess Maud. “I also note many German names in this notebook.” The person accompanying him then said: “Don’t be surprised. Here we see more English and more Germans than continental French.”

The Ajaccio climate would be the main factor in this winter tourism and foreigners did not fail to mention it. Miss Campbell would say that no climate is as pleasant as Ajaccio’s, whose most enjoyable months are January and February. “Corsica”, she would add, “is one of the few health stations where invalids may remain during the summer with benefit, as within a few hours of Ajaccio are several villages in the hills, offering all the advantages of Swiss mountain air, without the fatigue of travelling.” Foreigners expected a lot from this healthy climate. To get around, Miss Campbell recommended that her friends rent pony-drawn traps.

She reminded them, in this regard, that “In 1840 the island had only one route royale… Now there are nine routes impériales, thirteen routes forestières, five routes déparmentales, &c.” Hotels and accommodation were then in their infancy. Miss Campbell mentioned the Hôtel du Nord, the Hôtel de Londres, and the Hôtel de France, where she would regularly stay from 1869 onwards. These dilapidated and noisy guesthouse hotels could not have hoped to satisfy an affluent class accustomed to luxury and comfort. So it was when Miss Campbell began writing her book that the imminent construction of a new hotel on the Grandval course started to be discussed, from where one would enjoy a very beautiful view of the Gulf and the city.

Spearhead

of the Foreigners' Quarter

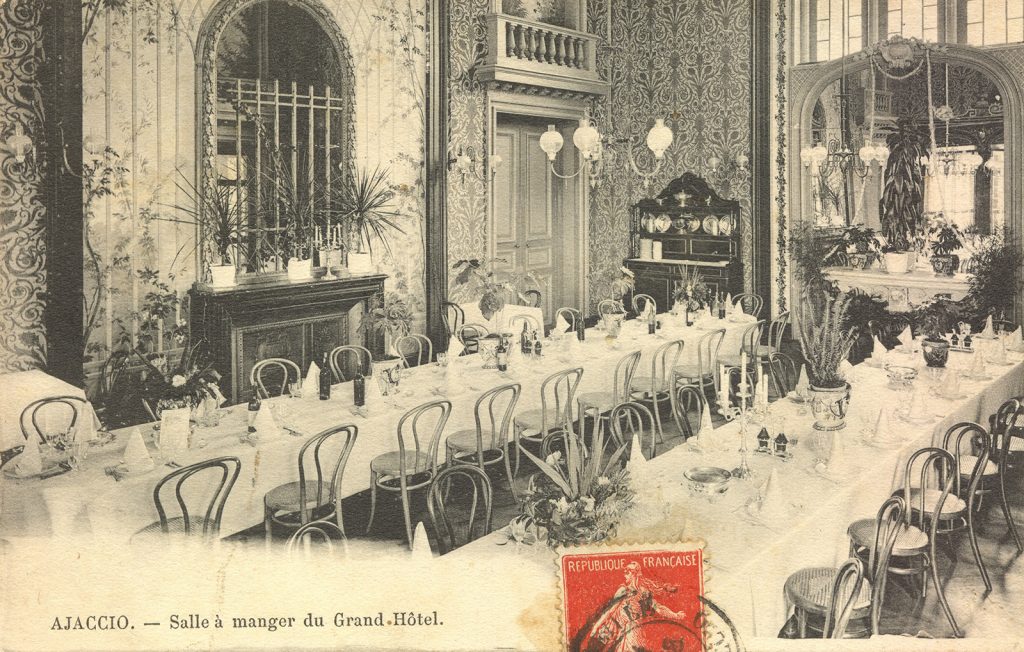

The Ajaccio Grand Hôtel et Continental was built between 1894 and 1896 by the architect Barthélemy Maglioli on the artery opened during the Second Empire to connect the Diamant to the Casone. It was thanks to Count François-Xavier Forcioli-Conti, who would pay for it, that it was built. The Swiss hotelier, Théophile Hofer, would manage it. In the centre of a 12,000 m2 park, the Grand Hôtel then had 100 luxurious rooms and lounges, a lavish dining room and a vestibule decorated with a trompe-l’oeil colonnade. Its equivalents at the time were the Winter Palace in Menton, the Carlton and Hyde Park Hotels in London, the Ritz Hotel in Paris, the Grand Hotel in Rome and the Frankfurterhof in Frankfurt.

Like a vast elongated rectangle

The building appears like a vast elongated rectangle. The building materials are plastered rubble for masonry facades, false quoins at the corners and granite for the columns of the entrance porch. The four-storey south front elevation consists of a central body bounded by two projecting bays that rise higher than the rest of the roofs.

The two wings are extensions of the central body, framed by bossed quoins. The façade is punctuated by double decorative bands.

The two projecting bays are finished with loggias formed by a semicircular arch supported by two engaged columns with Doric capitals. Above and below the loggias are garlands with floral motifs. In the upper part, there is a cartouche with a textured effect. Scrolled consoles support the entablature and, at the top of the roofs of the projecting bays, two pine cones indicate the gable.

The main entrance occupies the centre of the facade, consisting of an arcade with semi-circular arches, adorned with two cylindrical columns of granite with Ionic capitals. The balustered balcony of the first floor rests on this entablature.

To the right of the building, the annexe is connected to the hotel by the grand salon, whose façade is continuously bossed. The entrance to the annexe is distinguished by a porch with cast iron columns surmounted by a marquee and a railing also made of cast iron. The first floor bays are surmounted, in the central body, by curvilinear pediments supported by scrolled consoles.

***

Close in style to the hotels that were built on the Côte d’Azur at the same time, the new establishment offered its sometimes famous guests luxurious comfort, far from the pioneering era of 1860.

Here is a description by Victorien du Saussay: “The Ajaccio Grand Hôtel et Continental is the modern palace of the city. It rises above lush gardens, on the side of a green hill where the most diverse flowers and trees grow and bloom.

All its windows open to the South. It dominates the sea with a laughing majesty. From afar, it offers itself as a caravanserai of dreamland in its setting of giant palm trees.”

The internal distribution is not to be outdone. On the ground floor are the entrance hall, the dining room on the left and then the director’s accommodations on the right. All the service rooms are oriented to the North: kitchen, workshop, wine cellar, storerooms, sanitary facilities, etc.

The section connecting the annexe to the hotel serves as a breakfast lounge and leads to the ballroom. But it is the dining room that best testifies to the quality of the establishment. “The dining room is remarkable for its mirrors, fireplace and paintings. Everything is monumental. At the back, a statue of a woman holding an oar represents the city of Ajaccio, under the inscription: “Napoleonia Civitas”, surmounted by the city’s arms and an eagle with its wings spread. (…) Lastly, above the gallery door is the orchestra’s semicircular platform.”

In 1903, the management of the Grand Hôtel d’Ajaccio and Continental passed into the hands of Paul Lafond-Prével, owner of the Hôtel de la Trémouille in Paris. It was he who modified the grand entrance hall, closing the space with huge glass doors, creating a true winter garden. The hotel would then belong to Maurice Prével, who also owned the Grand Hôtel de la Paix and the Hôtel Méditerranée in Nice.

A prestigious clientèle

The lists of winter visitors published in the local press of the time abounded with princes, counts, barons, Austrians, Germans and English, but also Parisians – the same aristocratic clientèle as that of the Côte d’Azur. A clientèle that would establish the reputation of the Ajaccio Grand Hôtel et Continental.

The most prominent European personalities of the time frequented the establishment. One would see there the Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, Franz Joseph I of the Habsburg dynasty, as well as his wife, Amélie-Eugénie-Elisabeth of Bavaria, known as “Sissi” or the writer Jozef Konrad Korzeniowski, known as “Joseph Conrad”, author of “Lord Jim” and “Heart of Darkness” among other works. In 1902, for four weeks, His Royal Highness Duke George II of Saxony-Meiningen stayed there, and left satisfied with his health, but not before having distributed decorations to the city’s officials in gratitude for the warm welcome he had been given. If this building was able to contribute to the development of the city during the Second Empire and the Third Republic, it was of course due to its owners who were among the most enterprising Ajaccio hoteliers. “They are developing,” writes Francis Pomponi in the book “Histoire d’Ajaccio”, “a more refined tourist product, adding to the charm of their accommodation facilities – vast salons, spacious rooms with baths, exotic gardens, shaded terraces, lush baroque settings… again following the Côte d’Azur model – the stay in the mountains, at La Foce de Vizzavona (…)”

A certain Théophile Hofer

But it would be an insult to the truth to forget the eminent role played in the international reputation of the Ajaccio Grand Hôtel et Continental by its manager, the Swiss Théophile Hofer. In 1880 he had bought the Germania, a hotel opened in 1868 at number 10 of the Cours Grandval by a certain Gerhard Dietz, a native of Hanover. A hotel where, according to a witness of the time, one could encounter “a long procession of freshly turned-out ladies, and gentlemen riders who, having come to Ajaccio sick and tired, had regained robust health and seemed to have a no less robust appetite. French, Germans, Russians, Poles, Italians, Austrians, Spaniards rub shoulders and take their places next to each other, without worrying about the hatreds and grudges of politics (…) Dietz has solved a problem that they vainly try to resolve in the richest hotels in Nice and the Mediterranean resorts: elegant and comfortable life at a bargain price.”

The first act of the new owner would be to change the name of the establishment, which would then become the “Hôtel Continental” without losing anything of its reputation. On the contrary, since, according to the Guide Joanne, “the establishment offered all the comforts of first-class hotels: French cuisine and premium wines, meeting room, library, smoking room, garden and vast olive groves adjoining the hotel. Prices were moderate. A doctor was available to guests within the hotel grounds and special care for the sick was provided.”

When, in 1896, Théophile Hofer agreed to take over the management of the Ajaccio Grand Hôtel et Continental, the former “Germania” Hotel became an annexe to the Grand Hôtel and its vast hall was converted into a party hall. “It is here that the balls organised by the foreign colony to break the monotony of winter life will take place.”

While more and more luxury yachts regularly visited the port, balls and receptions, hosted by the Grand Hôtel’s Italian orchestra, brought together in the hotel’s lounges the foreign aristocracy and personalities of Ajaccio’s high society. Just like in the Ariadne pavilion, which was an annexe to it and welcomed this same public to Barbicaja beach.

The people of Ajaccio welcomed winter guests to all their parties: balls at the Grand Hôtel and the homes of the prefect, Viscount Sebastiani or Jean Lanzi, a wealthy merchant. They also attended concerts held at the Grand Café Napoleon.

A situation that greatly satisfied Dr Bennet: “At Ajaccio there is a nucleus of very good society, both Corsican and French. There are the préfet, the judges and magistrates, the officers of the garrison, the leading engineers, and the resident native families. All appeared to be most amicably and cordially disposed to strangers.”

It was in this euphoric atmosphere that the Ajaccio Grand Hôtel et Continental – like the Tour d’Albion, Miss Campbell’s residence bequeathed to Lord Bradshaw – would become the leading landmark of Ajaccio high society during the two decades before the Great War.

The seat of the

Collectivity of Corsica

Established by the law of 2 March 1982 on the special status of Corsica, the headquarters of the Corsican Region is temporarily housed at Villa Pietri, in Casone, and the Corsican Assembly, then presided over by Prosper Alfonsi, holds its sessions at the Palais Lantivy.

Ajaccio was declared the regional capital in 1983, and the decision to create a new building to house its institution was taken; however, given the urgent need to meet the requirements of the regional administration, the “Grand Hôtel et Continental”, then owned by the Raccat family, was rented.

In August 1984, Jean-Paul de Rocca Serra, then President of the Corsican Assembly, expressed the wish that the Region be able to establish itself in a building that it owned. In 1987, he decided to settle the debate by convening a meeting of the Corsican Assembly to adopt a resolution on “the establishment of the seat of the Region”. At the same time, negotiations were initiated with the owners of the “Grand Hôtel” who agreed in principle to a transfer, on the eve of the meeting of the Corsican Assembly on 25 January 1988. It confirmed its deliberation after a historic debate that took place in a tense atmosphere by “designating Ajaccio as the location of the Regional seat”. The acquisition of the buildings and the park took place in two stages. An architectural project to bring services together through the creation of additional buildings was devised by the regional architect François Van Cappel de Prémont and developed by the Guidicelli studio.

In 1990, the façade and gardens were included in the Supplementary Inventory of Historic Monuments, confirming the determination to preserve the original architectural quality of the façades.

From 1992 to 1996, the first phase of expansion was carried out with the creation of a building located to the rear of the former “Grand Hôtel” mainly to house administrative services, and the design of the new debating chamber.

As for the old buildings, they were completely refurbished between 1996 and 1998 and house the offices of the Presidents of the Executive Council and the Corsican Assembly as well as the offices of the political groups.

The debating chamber

What is remarkable is the spirit in which both the rehabilitation work on a surface area of 4,200 m2 and the extension work on 8,300 m2 of the old building were carried out, as everything was done to preserve the site and create a beautiful harmony between the existing buildings and the workspaces. The debating chamber, however, is the most remarkable architectural element of the extension. Round in shape, it finds a balance between the tribunes of the two presidencies, the benches reserved for councillors, and the places available to the press and the public. As a result, “in a circle everyone is at the centre” and debates are facilitated. The design of its granite and parquet floor in the form of a rosette accentuates this effect. The materials: leather, wood, granite and stucco, also give the space a refined and timeless atmosphere. Nothing has been left to chance, and this is true until today, when modifications have been made to allow the presence of more councillors (63 instead of 51) – following the merger of the three collectivities on 1 January 2018 (the two former Departmental Councils and the Corsican Territorial Collectivity) – without disturbing their harmony.

Discover the gardens

Everything you need to know about the gardens and their history, botany, etc.